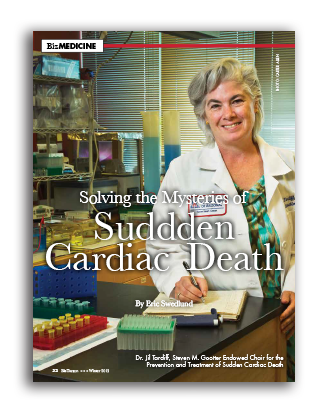

Solving the Mysteries of Suddden Cardiac Death

By Eric Swedlund

Dr. Jil Tardiff had her career in biomedical research steered toward endocrinology until a patient suffered a sudden cardiac episode.

Resuscitating the patient, doctors discovered she’d developed an enlarged heart, and from that moment on, Tardiff devoted her efforts to studying hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or HCM, which affects one in 500 people and is one of the most frequent causes of sudden cardiac death.

Tardiff’s chief goal became understanding HCM’s mysterious and complex cellular and genetic mechanisms and the disease’s mutations in heart cells. It’s what drove Tardiff to the top of her field at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in Bronx, N.Y., and subsequently drove the University of Arizona Sarver Heart Center to recruit Tardiff as the first Steven M. Gootter Endowed Chair for the Prevention and Treatment of Sudden Cardiac Death.

“There is something about these patients that often really grabs you and that’s what happened to me,” Tardiff said.

A dual M.D. and Ph.D., Tardiff said her background in both the lab and the clinic gives her “translational heft” and credibility in both arenas of basic scientific research and patient treatment and care.

“Because I actually see these patients, it gives me insight to the true clinical condition that I want to study,” she said. “This is the whole concept of medicine as an art – and it comes from interacting with patients and realizing what you learn in books is only the starting point and every single patient is different. Most of my patients are the exception, not the rule. And that’s the conundrum.”

The devastation inherent in sudden cardiac death is its unexpected and abrupt onset. In a moment, without warning or indication, seemingly healthy people can fall dead.

Steven Mark Gootter was one such victim, a vibrant and athletic 42-year-old man. On Feb. 10, 2005, he woke early as usual and took the family dog for his morning jog. Gootter, a non-smoker with no history of heart disease and no prior warnings, died of heart failure.

In his memory, Gootter’s family began the Steven M. Gootter Foundation, with a mission of both research support and public education regarding sudden cardiac death.

“The foundation’s mission is to prevent sudden cardiac death and to find a cure for this insidious disease,” said Gootter Foundation President Andrew Messing. “We need to make people aware of how common sudden cardiac death is. Every now and then you hear of a celebrity. But it’s happening every day to men, women and young people around us.”

Remembering Gootter as a “people magnet,” family man and entrepreneur, the foundation set its sights on raising money to support research. In March, after seven years of fundraising, the Gootter Foundation reached its goal of $2 million to establish the endowed chair.

“The foundation feels really lucky and fortunate that the Sarver Heart Center found Dr. Tardiff. She is really perfect for the position,” Messing said. “Dr. Tardiff has the drive and the passion and the intellectual prowess to really make a difference in sudden cardiac death research. We really couldn’t have found a better candidate.”

Dr. Fernando Martinez, director of the BIO5 Institute and the Clinical and Translational Science Institute, said Dr. Tardiff’s strengths as a physician scientist represent an increasingly critical aspect of academic medicine.

“Dr. Tardiff’s work as a cardiologist has made her innately aware of how tragic sudden cardiac death is. Therefore, she decided as a scientist that she will find a cure for those cases caused by rare genetic mutations. Her background allows her to apply her research in a clinical setting, and work collaboratively with experts in related fields here at the UA, which has already facilitated success towards this important endeavor.”

While Tardiff said it’s her long-term goal to establish the southwest’s first HCM clinic at the UA, the university has been a fruitful place for her research from day one, thanks to the Gootter Foundation’s support.

“The bottom line is having that sort of support behind me gives me freedom, especially at a time when the NIH is contracting. What the endowed chair means to me is I have funds set aside to walk out on the edge and that’s where the great stuff is going to be done,” she said. “Having this sort of support lets me be as creative as I can possibly be. It allows me to take intellectual risks and that’s where this disease needs to go.”

Tardiff’s research approaches HCM from the biophysical side, seeking to understand the relationship between genetic mutations and cellular mechanisms in damaged hearts – and why not every outcome is the same.

“There’s no obvious reason why mutations or changes should cause such a complex and often devastating endpoint. The genotype link to the phenotype is not a straight line,” she said. “The challenge we all face can be boiled down to one problem – we cannot at this point in time, for most of these mutations, decide or predict what will happen to the patient based on the genetic determinations. This is a catastrophe because it limits what we can do when we identify these patients.”

Scientists have known about the genetic drivers of HCM for 20 years, but the disease’s complexity has made for slow progress and humbling research.

“The opportunity to do good, to really make a difference, is high. Once we can start using these genotypes to tell people what their endpoint will be, then we can develop therapies to help push that endpoint off, to prevent episodes,” Tardiff said.

Currently, people from families with multigenerational sudden cardiac death can be identified as high risk, often as children or adolescents. But the mainstay treatment is an implantable defibrillator, which is expensive and hardly a panacea.

“We know this disease is progressive,” Tardiff said. “These big, misshapen hearts happen over time. If we understand this early process, maybe we can change the natural history of the disease instead of saying ‘Here’s your defibrillator, good luck to you.’ ”

HCM is a profoundly complex disease. Family members with the same genetic mutation might have hearts that look different. The key for researchers like Tardiff will be coming up with early diagnoses and learning how the disease progresses.

“We’re getting to the point where we’re asking the right questions. The science, the whole field, is getting more focused. There’s a lot of enthusiasm about what we can do when we identify people before the end stages of the disease,” Tardiff said. “What’s held us back until this point is that the disease is so progressive, so it depends on when you look. Snapshot science in cardiology is a difficult thing. What the heart looks like today may be very different five years from now and it makes the disease challenging.”

Scientists have identified more than 1,000 different HCM mutations and Tardiff’s own specific focus is on a particular subtype in which the genetic mutations don’t lead to enlarged hearts, yet the incidence of sudden cardiac death remains high.

“It isn’t just the link between having a huge heart and sudden cardiac death,” she said. “This subset is not as obvious and I thought it was very interesting from the beginning. Why that disconnect? To my mind what that meant is there is a cellular process we’re missing – and that’s something I’ve spent the last 15 years trying to understand.”

Bringing Tardiff to the UA was a huge win for Martinez and Dr. Gordon Ewy, director of Sarver Heart Center. She admits it wasn’t an easy recruitment, but that at the UA she sees unique opportunities and the potential for a great HCM clinic.

“I found in talking to people here a true sense of adventure,’’ Tardiff said. “In many places now, because of NIH funding there’s a retrenchment. But no one here is really interested in standing pat right now. That’s energizing.”