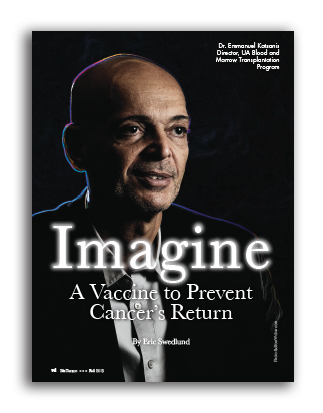

Imagine a Vaccine to Prevent Cancer’s Return

By Eric Swedlund

Imagine a vaccine created from the cancer cells of a child that could prevent the disease from ever coming back.

That is the goal of doctors at the University of Arizona Steele Children’s Research Center.

Helping to fund this critically important research is a recent $537,230 grant from Angel Charity for Children.

Dr. Emmanuel Katsanis, section chief of pediatric hematology, oncology and blood and marrow transplantation as well as director of the UA’s Blood and Marrow Transplantation Program, says the grant will fund clinical trials and aid in the expansion of research in pediatric cancers.

Each year, Steele Center research physicians diagnose about 60 new pediatric cancer patients, who are added to the hundreds of kids with cancer and blood disorders that they treat and provide long-term follow-up care at The University of Arizona Medical Center – Diamond Children’s and its affiliated clinics.

“We are profoundly grateful to Angel Charity for this gift,” said Dr. Fayez K. Ghishan, head of pediatrics, director of the Steele Center, and physician-in-chief at Diamond Children’s. “We will be able to triple the number of clinical trials available to our children suffering with cancer.”

Leading some of the most promising Steele Center research projects is Katsanis, who came to the UA in 1997 from the University of Minnesota, where his oncology fellowship was influenced by UM’s strong immunology research.

“Even though I was an oncologist, the field of immunology seemed very exciting at that time,” Katsanis said. “New therapies were being used in humans with activated cells.”

When he arrived at the UA, Katsanis set up his lab with a post-doc fellow who had a background in biochemistry.

“A lot of times, it takes two people with different backgrounds to come up with something,” Katsanis said. “Between the two of us, we came up with this vaccine.”

Katsanis is the principle inventor of Chaperone Rich Cell Lysate, or CRCL, a vaccine developed from a patient’s own cancer cells that is predicted to prevent cancer recurrence.

“In most cancers, we can induce cancer remission. If the cancer returns, the chance of survival decreases exponentially,” Katsanis said. “Angel Charity’s grant will propel pediatric cancer research forward. We are all excited to move basic and translational cancer research at the Steele Center to the highest level.”

To develop the CRCL vaccine, Katsanis began his research by taking a mouse tumor – leukemia for example – and breaking up the cells to isolate the breakdown products. Some fractions are very rich in chaperone proteins, which exist in all cells to pick up the smaller particles of proteins called peptides and move them around.

In a tumor broken down to 20 fractions, for example, four or five fractions would contain high levels of chaperone proteins. Those chaperone protein-bound peptides may generate an immune response and be used to make a vaccine.

Like bacteria, however, tumors find ways to resist the vaccine. One advantage of Katsanis’ vaccine is that researchers don’t need to identify what specific peptide the tumor expresses in order to fight it.

Katsanis envisions a cancer treatment one day that could use the very tumors attacking patients to create vaccines to fight the cancer.

“We feel there are unique peptides in everybody’s cancer, so this vaccine will work better if it’s taken from the patients’ own cancer cells,” he said. “But it’s hard to imagine large pharmaceutical companies interested in preparing unique vaccinations for each patient.”

Katsanis said he would anticipate that drug companies may be interested in pooling specific patient tumors until perhaps a large enough group could be discovered to make the vaccine universal.

Katsanis has published his results on a variety of cancers in mice – leukemia, lymphoma, melanoma, sarcoma, neuroblastoma and breast cancer.

Another challenge is cancer’s ability to suppress the immune system as a way to defend itself. Cancer’s immunosuppressive maneuvers essentially form a shield so that white blood cells called T lymphocytes won’t be capable of attacking the cancer.

“It’s not enough to be able to activate an army of T lymphocytes – you also have to find a way to disarm the cancer to allow these T cells you’ve stimulated with the vaccine to work,” Katsanis said.

As a pediatric oncologist, Katsanis knows that pharmaceutical companies are primarily interested in adult cancers that impact the largest number of patients. His goal is to bring forward clinical trials in both adult and pediatric patients.

Once a cancer has gone into remission through traditional therapies, the vaccine could be applied to perform “mop-up” work, ensuring against a relapse. The vaccine would essentially educate the immune system to focus on attacking any cancer cells left behind.

The Angel grant will enable Katsanis to bring two more post-doctoral research fellows into his lab, as well as begin establishing the support infrastructure necessary to hold clinical trials in Tucson.

“We developed it here, we’d like to see something happen here at the University of Arizona,” said Katsanis, who’s hoping to see clinical trials begin within the next three years.